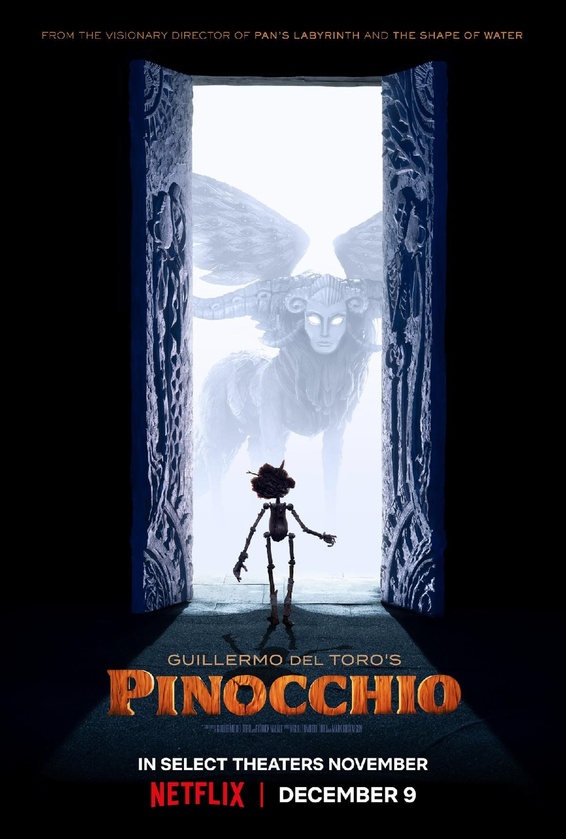

In his newest film, 'Pinocchio,' Guillermo Del Torro mesmerizes his audience with stunning visuals and performances. He honors the source material that most of society is ignorant of. All while gutting two quintessential themes of payoff and meaning.

Widely considered the king of modern movie monsters, Del Torro uses his directorial eye, trained for the weird and unnerving, to create some of the most unsettling visuals in a children's movie to date. Everything from how Pinocchio moves when he is first given life to the odd use of the many-eyed seraphim that replaces the role of the fairy, each shot carries an air of innocent macabre. The gorgeous design of the stop-motion world lends itself wonderfully to this unsettling feel, bringing laughter and horror in equal measure during sequences like Pinocchio burning his feet off or his visit to the coffin and decay-ridden afterlife when he dies (and no, you didn't misread that.)

These choices not only subvert our expectation of the film, an expectation set primarily by our memories created by Walt Disney's original 1940 adaptation by the same name, but act as a subtle nod to the source material The Adventures of Pinocchio penned in 1881, by Italian author Carlo Collodi; a source material whose dark subject matter and execution remind us much of the Brother's Grimm fairytales. Though Del Torro chooses to avoid dark topics that Walt Disney took in stride (mainly the sinful crime of child trafficking), there are still plenty of maturities to explore.

A creative and compelling change that Del Torro makes to the classic tale is the inclusion of World War One and World War Two as a backdrop that goes hand in hand with Geppetto's backstory, another welcome and creative deviation. Not only does the backdrop of the wars help raise the stakes for our characters and provide plot devices with which to solve their problems (Monstro brains for dinner, anyone?), but it also creates a compelling story arch for Geppetto as he goes from trying to replace something he lost to accepting Pinocchio for who he is. One could argue that Disney's choice to have Geppetto create Pinocchio out of an honest desire for a son is more compelling as a motif, ultimately showing boys that fathers should desire to have sons. However, as far as the sins of creative license go, this hardly counts, and even the most stalwart Disney enthusiasts will struggle to see an issue.

Sadly the film fails us in two significant ways, and both occur (as most Hollywood sins do) in the script.

First, the major flaw of Pinocchio being a habitual liar and needing to overcome this flaw on his journey to becoming a 'real boy' is downplayed to the point that the growth of his nose, and the lies necessary to do so, are glorified rather than condemned. Spoiler warning: this occurs because the growth of Pinocchio's nose is used to create a bridge that our protagonists utilize to reach Monstro's blow hole and escape. The messaging here has changed: instead of lies being an extreme taboo and honesty always being the best answer, Del Torro shows us that lying is acceptable if it gets you out of a tough situation. This choice is even sanctioned by Pinocchio's father, Geppetto, saying, "Just this once," showing us that even he knows this choice is wrong and is choosing to set aside his morality for the sake of saving his neck rather than encouraging his son to come up with a different solution that saves them without compromising a key value our society should cherish.

Lastly, (and spoiler warning for this par too) we never get the satisfaction of Pinocchio becoming a real boy. That's right, in a movie driven by a wooden boy's desire to become real, and therefore setting out on a journey to prove that he has the qualities necessary to become a real boy (I.e.- honesty, bravery, compassion, self-sacrifice, etc.), our main protagonist never achieves this most essential of goals.

There are two ways someone could justify this incredible flaw in storytelling:

First, since Pinocchio chose to lie to escape Monstro, he does not actually deserve to become a real boy. The film contradicts this because of the second explanation. The film espouses that the mark of a real boy is not the way one looks but rather the ability for one to die, a law of nature that Pinocchio continually subverts throughout the movie in yet another new plot device. To save Geppetto from drowning after escaping Monstro, Pinocchio breaks a rule placed on his immortality and becomes 'mortal' though still made of wood. The issue here is similar to the sin of showing a gun hanging on the wall, yet after the entire film, the gun still hasn't gone off. Why was it there? The same goes for Pinocchio. Suppose he's made all the necessary sacrifices to become a 'real boy,' with the magical prospect of such looming just beyond the audience's sight. Why not give them the satisfaction of seeing Pinocchio become real? Especially after having promised audiences this was the end goal the whole time.

Though the ending falls flat, Guillermo Del Torro's Pinocchio is still a visual achievement, the likes of which have not been accomplished since Tim Burton's A Nightmare Before Christmas. It is gorgeous, staffed with an all-star cast, and brimming with detail that you do not want to miss. Just be prepared to ultimately be let down as the curtain falls and the fate of our still wooden boy is left unknown.

If you enjoyed this article, consider subscribing! Every dollar helps us create new narrative content with better writing so that major plot issues like you read about above stop happening! Click the button below and become a Forerunner today.